The Big Balloon grew of out of memories of a giant black balloon — used to pack railroad cars that weren’t full to keep the cargo from shifting — given by a family friend who worked at a nearby mill. It provided endless ours of laughter, inventive games, and a few tears. The story came out in print and digital formats in Door is a Jar Magazine. Paperback copies and Kindle edition are available at Amazon. It contains writing from 36 contributors from all over the world.

The Big Balloon

by

J. Edward Kruft

It was meant for train cars, inflated to keep the freight from shifting during travel. Shifting. Good word.

We used it as a backyard toy: something to jump on, roll across the lawn like a lumberjack on a river log; something to bounce off of, pound fists into. When it was fully inflated, it was three feet high and five feet across and was at once billowy and taut. Sometimes – often – we’d render it half flaccid so that one of us could sit on the far end, pushing all the air to the other end, all but begging the other of us to jump on its bulbousness and send the sitter flying into the air.

One Toke Over the Line played on the old clock radio sitting atop the Weber grill; its lyrics embarrassed us in front of the grownups (in private we loved to sing along and pinch our thumb and forefinger before pursed lips and slit our eyes) and so we called to our father: “Come on, do it, do it!” Brian went first. As he flattened the far end, Dad readied himself and fell backward onto the side swollen with air.

Admittedly, Brian’s performance wasn’t stellar. Still, Mom didn’t need to say what she said in front of company.

“I tell you Brian, if you lost that baby fat you’d be able to go a lot higher. Chris, you go. Show your brother.”

I sat and flattened the far end, Dad, somewhere behind me. I didn’t know he had decided to launch himself from the railing of the deck. I looked down on the roof of our house. I remember thinking, in that nano-second before consciousness became my enemy and drained the pigment from my face: “wow, there’s a lot of moss up here.”

Gasps from the grownups.

Sittin’ downtown in a railway station One toke over the line…

SNAP!

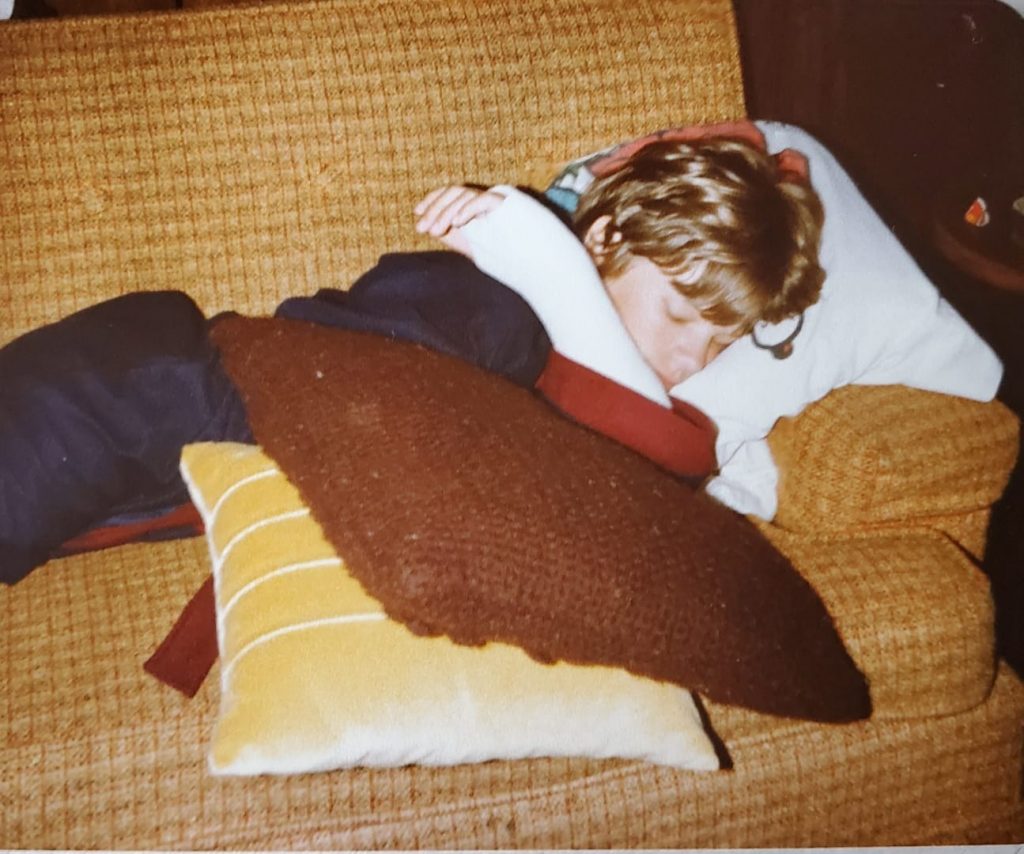

That winter, a good three months after the cast was removed and I could finally scratch without a coat hanger and Brian had stopped making fun of how scrawny my left arm was compared to my right, we let the air out of the big balloon and took it to the hill behind the school and we – Me, Brian, Carla, and Max – rode that giant mass of rubber down the hill in the snow. Over and over and over. Carla was on the front and I saw the massive backside of Jake Weir and when Carla’s face came in high-velocity contact with that massive back, the snow went red.

My father was the volunteer fireman on duty. He handled Carla so deftly, calming her sobs, collecting her teeth and packing them – roots still attached – in clean snow (intentionally he walked a distance from the accident to find snow unmolested). I found myself saying to a kid I didn’t know: “That’s my dad.” If he saw me standing there, he didn’t betray the fact. He was busy. He was important. Important. There’s a word.

By 8th grade, Brian and I sat nearly every day in the abandoned, horseshoe shaped arena, out through the woods at the Old Riding Academy, and got stoned. Brian always had pot. I don’t know where he got it. He might have grown it himself for all I knew. Brian and I were close in that we were brothers – Irish twins, at that – but we weren’t at all close in the really-talking-to- one-another sense. Which was mostly cool. But it made it all the more surprising, as I passed the joint back to Brian, that I saw tears. He noticed my notice and turned away.

“What?” he asked.

I shook my head, looking to my lap. “Nothing.”

Later, heading home through the woods, super stoned (if Brian did grow his own shit, he was a horticultural genius) I asked him: “You okay?” His answer was to walk faster, outpace me, and eventually, he broke into a jog.

When I got home, his bedroom door was closed and so I went out back in order to evade my mother’s why are your eyes so bloodshot inquires. The balloon was flat. I thought that strange. I could have swore it was completely inflated when I glanced it from my bedroom window the day before. I walked over. It had been slashed. Not once, but thoroughly. It was slashed the way they say it in those 48 Hours episodes: up-close and personal. Up-close. Personal.

Much later, Dad was out on a call, thunder crashing against the moss on the roof. We turned off the lights, not so much in homage to him for the work he was doing in nasty conditions, but because Brian and I liked the idea of being without electricity in a storm. We played “Can’t Stop,” a game we got through the mail from cereal box tops. Mom was winning, her eyes glistening in the Yankee Candlelight.

The smell of saccharine cinnamon.

She held the dice for longer than was typical of her. “Listen, boys.” She put the dice on the table. “Your father and I. We’ve decided. We’ve decided that we.

“We’re getting divorced, boys.”

Brian and I looked at each other. I was the one to finally speak. “It’s your turn, Mom.” Divorced.

The big balloon stayed put, slashed and flat and sad, until the spring when Mom decided to redo the little patch of earth next to the garage. “I’m going to plant strawberries,” she declared. Brian and I helped her dig out the weeds and before we emptied the bags of fresh mulch she asked us to go grab the big balloon. Mom arranged it over the plot of land. “There,” she said. “That will keep the weeds from coming back.”

I looked to Brian, but he was looking at the ground. No one mentioned the slashes, not before, not now, and as we began heaping the fresh dirt atop, it was clear, not ever.